Archive

Explore the archive timelines

The October 2019 uprising has marked the historical geography of mass social mobilization in Lebanon. The scale, intent, and depth of this protest distinguishes it from previous revolts. The October 2019 uprising was exceptional but not singular. Lebanon has a deep history of bottom-up social mobilizations that have been foundational to the formation and constitution of the Lebanese state.

While histories of the country are often focused on the dynamics of external powers, sectarianism, and capitalism, contentious politics can no longer be ignored in the comprehension of political and social life in Lebanon. This online archive aims to demonstrate the historical depth of social mobilizations in Lebanon by showcasing some of the rapidly growing key literature, interviews, and archival documents.

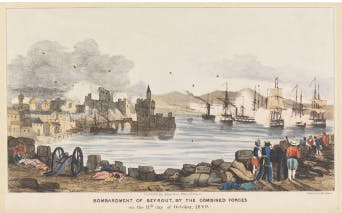

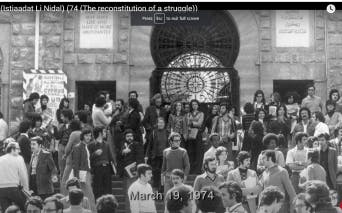

In this archive, we feature the series of popular revolts in the 1800s, known as the popular revolts or ‘Ammiyat. The ‘Ammiyat created a novel political agent, the “commoners” (‘amma), who organized as a political collective through gathering in crowds and creating pacts to make demands of the ruling elite. Much like in 2019, the central vector for the revolts of this period were tax rises, labor conditions, governance, and representation. During the French Mandate, Beirut emerged as the central locus for mass mobilizations. Labor unions, professional syndicates, political parties, and women organizations were formed creating a new kind of popular politics. Protests proliferated in this period and continued into the first decades of Lebanon’s newly-found independence. In 1958, the United States Marines intervened in Lebanon to preserve the established order of the country. Protests engulfed the country in the wake of the US intervention and helped push President Shihab to expand the developmentalist state.

The Civil War (1975-1991) impeded popular uprisings. But the post-war era, at the start of the 1990s, soon witnessed the proliferation of protests against the accelerating post-war reconstruction and working conditions more broadly. The significance of popular mobilization in shaping political life erupted onto the scene following the assassination of Prime Minister and billionaire Rafik Hariri with the Independence Intifada in 2005.

The Arab uprisings shook the region at the end of 2010 but did not provoke a mass social mobilization in Lebanon. Several protests erupted in the wake of the regional uprisings but soon petered out until 2015 in the context of a garbage crisis. The "You Stink" campaign resulted in some of the largest mass mobilizations in Beirut since 2005.

The influence of the 2005 Independence Intifada, the smaller protests, and mobilizations that occurred in the shadow of the Arab uprisings and the "You Stink" protests in 2015 are all directly evidenced in the October 2019 revolts. For instance, chants from the Arab uprisings, such as “the people demand the fall of the regime” were frequently heard in 2019. As was the chant from the 2015 "You Stink" protests, “All of them means all of them”. The establishment of tents, discussion forums, and the carnivalesque atmosphere that formed part of the protest had clear parallels in the previous protests that emerged in the post-war era.

But October 2019 also shows novel forms of mobilization that make it an exceptional moment for the country. Roads and highways had been blocked before as part of the protests in Lebanon but never with the speed and extent of 2019. Protesters rapidly brought the entire country to a halt and soon protests erupt not only in the heart of Beirut but across the country. October 2019 is exceptional and transformational not only for the number of protests and the extended time over which protests erupt but for the dispersed geography of the revolt. Downtown Beirut was the heart of the protest but for the first time nodes of social mobilization erupted all over the country.