The Arab Uprisings and You Stink

2010-2015

The momentum from the Independence Intifada of 2005 that erupted following the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri was soon thwarted by the July 2006 war and the mini-Civil War of 2008. In 2011, the Arab uprisings shook the region and resulted in the toppling of political leaders in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen.

The impact of these regional uprisings resulted in some limited protests in Lebanon. The Laique Pride parades and the “fall of the regime” campaigns pulled thousands of Lebanese on the streets of Beirut, if only fleetingly. But overall, social mobilizations in Lebanon that emerged in the wake of the Arab uprisings did not gather the momentum witnessed elsewhere. Activists could not agree on key political questions, such as reform versus revolution, how to address Hezbollah’s weapons or how to engage the uprising in Syria.

Tensions continue to build in Lebanon and were heavily impacted and directly implicated in the escalating violence in Syria. A large influx of Syrian refugees also resulted in a rise in tensions. Resentment in the country grew against the ruling elite and the increasingly dysfunctional governance system. Access and the provision of basic urban services and goods significantly deteriorated.

In 2015, the scale and intent of social mobilization rapidly expanded in the context of a garbage crisis.

The “You Stink” revolt (Tol’et el Rihetkun), involved a series of escalating protests that erupted in the summer of 2015, following the piling up of garbage on the streets of Beirut and beyond. At the core of this protest was a loosely formed network that became known as “You Stink”. This movement ensured that the garbage crisis was not engaged as an isolated event but framed as part of a broader collapse in governance that was rooted in Lebanon’s sectarian political system. Demands made by the “You Stink” network incorporated not only the immediate garbage crisis but also changes to the electoral system, such as an end to the majoritarian electoral law and the formation of a proportional representation electoral system.

The subsequent large-scale revolt that became known as the “You Stink” protest involved not only the “You Stink” network but a loose collection of activists joined by dozens of other groups that were referred to as al-hirak (the movement). The hirak included a wide range of political views and experiences, from liberals to communists, groups focused on women’s rights, disability, LGBTQ, human rights, and environment politics. It incorporated many groups that were associated with the protests that happened in the wake of 2011. These various groups had competing political visions and tactics. Their broadly horizontal leaderless formation soon resulted in confusion and conflict. On August 23, at the height of the protests, the “You Stink” movement even announced its withdrawal from the revolts carrying its name, as the violence between protesters and the security forces intensified.

The significance of the You Stink protest was that the divides within the hirak and the “You Stink” network did not prevent tens of thousands of Lebanese descending on downtown Beirut to protest. The anger at the ruling elite over the garbage crisis and all that it represented, was able to unite tens of thousands of Lebanese despite the continued and all too present differences between those within the same revolt.

After the protests died down, the most immediate impact of the “You Stink” protest was on the 2016 municipal elections and the rise of the municipal campaign Beirut Madinati. While Beirut Madinati was focused on Beirut it had a nationwide impact and provided a push to independent efforts against established political parties. They also propelled the rise of independent candidates in professional associations. The influence of the “You Stink” protest, and the experience of Beirut Madinati, was also clear in the October 2019 protests. One of the principal slogans of the October protests, “all of them means all of them” (kullon yani kullon), was one drawn directly from the “You Stink” movement. The significance of this slogan, Mona Harb(2018) has argued, was that for the first time post-2006, activists requested accountability in unambiguous terms across both March 8 and March 14 political camps for failed public services and corruption.

2009, Laique Pride was formed by a small group of young artists based in Beirut and Paris. This group aimed to hold regular parades to call for an end to the sectarianism and the establishment of a secular state. In these artist-activist led parades a deliberately festive atmosphere was created with flowers, balloons, drummers and clowns. The parades soon gained attention. In April 2010, the Laique Pride rally involved more than 5000 people marching through downtown Beirut.

December 2010, a poor street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi in the small Tunisian city of Sidi Bouzid ignited protests following his self-immolation that would sweep the Middle East.

Lebanon at the start of 2011 was convulsed in a political crisis following the withdrawal of Hezbollah and its allies from the government. On 27 February 2011, anti-sectarian activists who had been organizing regular protests achieved the first significant mobilization. The protests claimed that 20,000 turned up to protest against the sectarian system. These protesters demanded the downfall of the sectarian system and for a secular, civil and democratic state. Social mobilization continued but remained small and sporadic.

A small group of young artists start the Laique pride parades that incorporate various elements of play and festivity in Beirut under the banner of rejecting sectarianism and establishing a secular state. Photographer unknown, Creative Commons

Garbage piles up on the streets of Beirut in 2015 following the closure of the main landfill in the country. Photograph by Hasan Shaaban, 2015

Garbage bags piled up in Jdeideh, east Beirut, Lebanon. Photograph by Hasan Shaaban, 2015

The trash crisis had been a long time coming. Residents surrounding the Naameh landfill had protested since 1998, the year operations began. In 2015, Sukleen’s contract expired, and local residents ensured that the Naameh landfill was closed. There was no replacement, however, and a trash crisis ensued. Rubbish piled up on the streets of Beirut and Mount Lebanon producing a react of disgust and shame. A loose coalition of activists organized under the slogan of You Stink.

Garbage piles up on the streets of Beirut. Photograph by Hasan Shaaban, 2015

Garbage burns on the streets of Beirut. Photograph by Hasan Shaaban, 2015

The You Stink protest demands went beyond the immediate resolution of the garbage crisis to condemn the entire political class. Photograph by Hasan Shaaban, 2015

The violence by state security forces against protesters further fuelled the You Stink protests. Images of protesters being beaten by riot police were widely shared on social media and pushed more people to join the protest movement.

Riot police beat a protester. Photograph by Hasan Shaaban, 2015

Riot police push a women to the floor. Photograph by Hasan Shaaban, 2015

Water canon against protesters. Photograph by Hasan Shaaban, 2015

Protesters face off a water cannon. Photograph by Hasan Shaaban, 2015

Protesters and riot police clash. Photograph by Hasan Shaaban, 2015

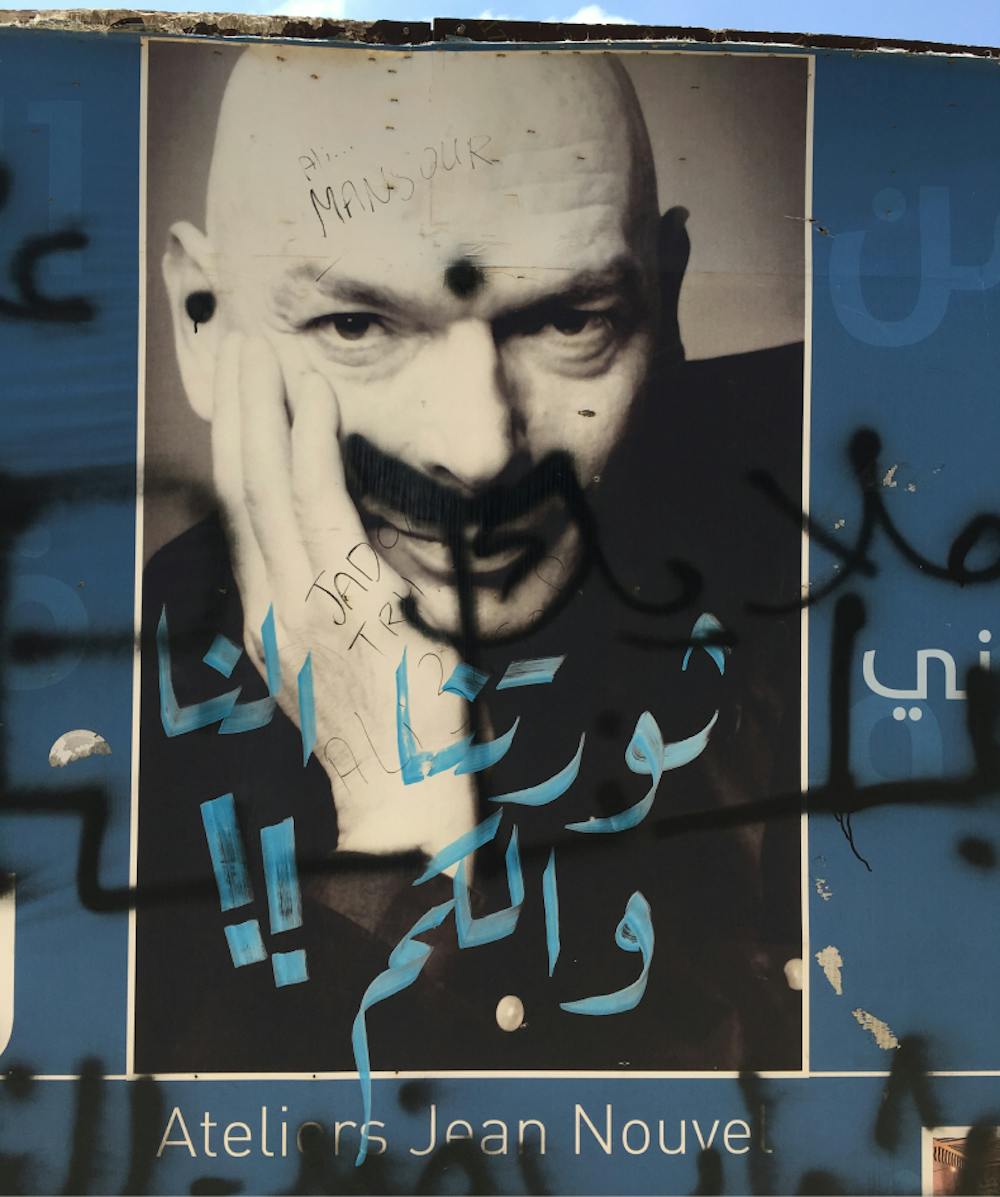

Graffiti on a new development by the superstar architect Jean Nouvel in downtown Beirut. The graffiti reads, “Our revolution for us, and for all of you”. Photograph by Deen Sharp, 2016

The You Stink protest focused in part of urban conditions.

The anger at the elite driven reconstruction of downtown Beirut that Rafik Hariri masterminded has long been a focus of ire for the Lebanese.

AbiYaghi, Marie-Noëlle, Myriam Catusse, and Miriam Younes, “From isqat an-nizam at-ta’ifi to the Garbage Crisis Movement: Political Identities and Antisectarian Movements”. In Lebanon Facing the Arab Uprisings, edited by Di Peri, Rosita, and Daniel Meier. London: Routledge, (2017).

Abu-Rish, Ziad. ‘Garbage Politics’. Middle East Report, Winter (2015). https://merip.org/2016/03/garbage-politics/.

Arsan, Andrew. Tal’it Rihatkum or ‘You Stink’ – On Waste and the Lebanese Body Politic [Chapter 8]. In Andrew Arsan, Lebanon: A Country in Fragments. London: Oxford University Press, (2018).

Baumann, Hannes. ‘Bringing the State and Political Economy Back in: Consociationalism and Crisis in Lebanon’. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics (2023): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2023.2188655.

Bray-Collins, Elinor. ‘Sectarianism from below: Youth Politics in Post-War Lebanon’. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, (2016). https://www.proquest.com/docview/1881549467/abstract/6C6DE157079744BFPQ/1.

Di Peri, Rosita, and Daniel Meier (eds). Lebanon Facing the Arab Uprisings. London: Routledge, (2017).

Fakhoury, Tamirace. ‘Lebanon against the Backdrop of the 2011 Arab Uprisings: Which Revolution in Sight?’ New Global Studies, 5 (2011). https://doi.org/10.2202/1940-0004.1136.

Geha, Carmen. ‘Politics of a Garbage Crisis: Social Networks, Narratives, and Frames of Lebanon’s 2015 Protests and Their Aftermath’. Social Movement Studies, 18 (2019), 78–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1539665.

Harb, Mona. ‘New Forms of Youth Activism in Contested Cities: The Case of Beirut’. The International Spectator, 53 (2018), 74–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2018.1457268.

Hermez, Sami. ‘On Dignity and Clientelism: Lebanon in the Context of the 2011 Arab Revolutions’. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 11 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9469.2011.01128.x.

İpek, Yasemin. ‘Entrepreneurial Activism’. American Ethnologist online first, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.13109.

Kaedbey, Deema, and Nadine Naber. 2019. ‘Reflections on Feminist Interventions within the 2015 Anticorruption Protests in Lebanon’. Meridians 18 (2): 457–70. https://doi.org/10.1215/15366936-7789750.

Khalaf, Samir. Heart of Beirut: Reclaiming the Bourj. London: Saqi, (2013).

Khneisser, Mona. ‘The Marketing of Protest and Antinomies of Collective Organization in Lebanon’. Critical Sociology 45 (2019), 1111–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920518792069.

Kraidy, Marwan M. ‘Trashing the Sectarian System? Lebanon’s “You Stink” Movement and the Making of Affective Publics’. Communication and the Public, 1 (2016), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047315617943.

Musallam, Fuad. Failure and the Politically Possible: Space, Time and Emotion among Independent Activists in Beirut, Lebanon. PhD Thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science, (2016).

Musallam, Fuad. ‘“Failure in the Air”: Activist Narratives, in-Group Story-Telling, and Keeping Political Possibility Alive in Lebanon’. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 26 (2020), 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.13176.

Musallam, Fuad. ‘The Dissensual Everyday: Between Daily Life and Exceptional Acts in Beirut, Lebanon’. City & Society, 32 (2020), 670–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/ciso.12349.

Nucho, Joanne Randa. ‘Garbage Infrastructure, Sanitation, and New Meanings of Citizenship in Lebanon’. Postmodern Culture, 30 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1353/pmc.2019.0018.

Rønn, Anne Kirstine. ‘The Development and Negotiation of Frames During Non-Sectarian Mobilizations in Lebanon’. The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 18 (2020), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2020.1729533.

Sengebusch, Karolin. ‘“It Is Not Politicized. But of Course It Is Politics”: Unconventional Forms of Lebanese Anti-Sectarian Activism’, Forum Transregionale Studien, (2012).

Sharp, Deen. ‘Beirut Madinati: Another Future Is Possible’. Middle East Institute, (2016), https://www.mei.edu/publications/beirut-madinati-another-future-possible.

Sharp, Deen. Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon: Corporate Urbanization. PhD Thesis, City University of New York, Graduate Center, (2018).

Sharp, Deen and Claire Panetta (editors). Beyond the Square: Urbanism and the Arab Uprising. New York, Urban Research, (2016).