Independence Intifada

1990-2005

The 1990s marked the formal end of the Civil War. The political and economic situation remained febrile and a financial crisis resulted in many – albeit modest in scale – strikes and protests. In 1992, Omar Karami resigned and Rafik Hariri was appointed as Prime Minister. Hariri’s plans for the new post-war Lebanon started to materialize. This involved the reconstruction of the Beirut Central District led by the Prime Minister Rafik Hariri’s urban development corporation Solidere and a broader neoliberal transformation of the country’s political economy (Baumann 2017).

Throughout the 1990s, notable strikes occurred in opposition to Hariri’s neoliberal economic policies and around working conditions more broadly (Majed 2020). Social mobilizations do not make up a significant political force in the 1990s and this is a period in which trade unions lost the ability to make independent demands of the political elite (Baumann 2016). In 1993, Rafik Hariri introduced a ban on street demonstrations. The spectre of slipping back into Civil War shadowed the country that still had to contend with the Israeli occupation in the country's south and the continued presence of Syrian troops. Notably, protests in the early 1990s often organized around pro-Palestinian issues and regional politics (Majed 2020).

In the early 2000s, Lebanese began to air their growing resentment over Syrian control in Lebanon. Several small but significant protests erupted in this period calling for Syrian troops to leave the country. In 2005, a seismic political shift occurred and a mass social mobilization transformed the politics of the country resulting in the ejection of Syrian troops in the country.

February 14, 2005, a massive explosion resulted in the murder of Rafik Hariri. In the wake of Hariri’s assassination thousands of people camped in downtown Beirut demanding justice and the withdrawal of Syrian troops. On March 5, Assad announced the withdrawal of Syrian troops from Lebanon. In response, on March 8, the Shi'i parties of Hezbollah and Amal led the organization of a farewell and thank you party for the Syrian troops, in Riad el-Solh Square in downtown Beirut. Days later, on March 14, centred in Martyrs' Square in downtown Beirut, those associated with Hariri celebrated the departure of the Syrian army. While the core of the protest was driven and organized by political factions close to Hariri the outrage over his assassination resulted in a social mobilization far larger than these groups. Estimates of the number of protesters of March 14 indicate as many as one million people gathered in the heart of Beirut, possibly a quarter of the entire Lebanese population.

In the March 14 protest, a clear nationalist emphasis was evidenced. Lebanese flags dominated the protest bringing together protesters who were otherwise not politically or socially aligned. A protest camp was organized in Martyrs’ Square by the grave of Hariri. The March 14 protest, and the small series of protests that followed, became known as the Intifada al-istiqlal, the Independence Uprising. A central call was to freedom in politics and Independence from Syria. The truth (haqiqa) and the slogan “nurid al-haqiqa” (we demand the truth) – about Hariri but also all the crimes of the past – become central to the protest movement (Haugbolle 2006). Following the assassination, the two squares in downtown Beirut (Riad el-Solh and Martyrs’ Square) became the focus of political life. Sit-ins lasted for months, and political demarcation lines were redrawn through intensified street protests (Majed 2021).

The singing of the Ta’ef Peace Accord in 1989 and the ending of open conflict in 1991 ushers in the post-Civil War era in Lebanon. Tensions remain high in the country despite the end of open conflict. Protests erupt around the Ta’ef Peace Accord and some violent clashes between rival political factions continue. In 1992, Prime Minister Rafik Hariri initiates the reconstruction of downtown Beirut and the country more broadly.

In 1994, Hariri officially launches the corporation Solidere to lead the rebuilding of the downtown area of Beirut. The joint-stock corporation Solidere resulted in this company becoming the sole owners of all real estate properties in the Beirut Central District. The transfer of the entire area of downtown Beirut to a corporation is highly controversial and small protests occur throughout the 1990s in opposition to this development scheme. In May 2000, Israeli occupation ends in south Lebanon.

Following Rafik Hariri’s assassination, the Hariri family refused the offer of a state funeral and insisted on a public affair. The family buried Hariri on a small plot of land next to the Muhammad al-Amin mosque that Hariri financed and is located in the heart of Beirut in Martyrs’ Square. Rafik Hariri’s Memorial Shrine, Wikimedia, September 2005.

An image from Martyr’s Square where in Arabic it is written “We demand the truth” that was a central slogan of the 2005 protest. Photograph by Petteri Sulonen, 2005 (Creative Commons).

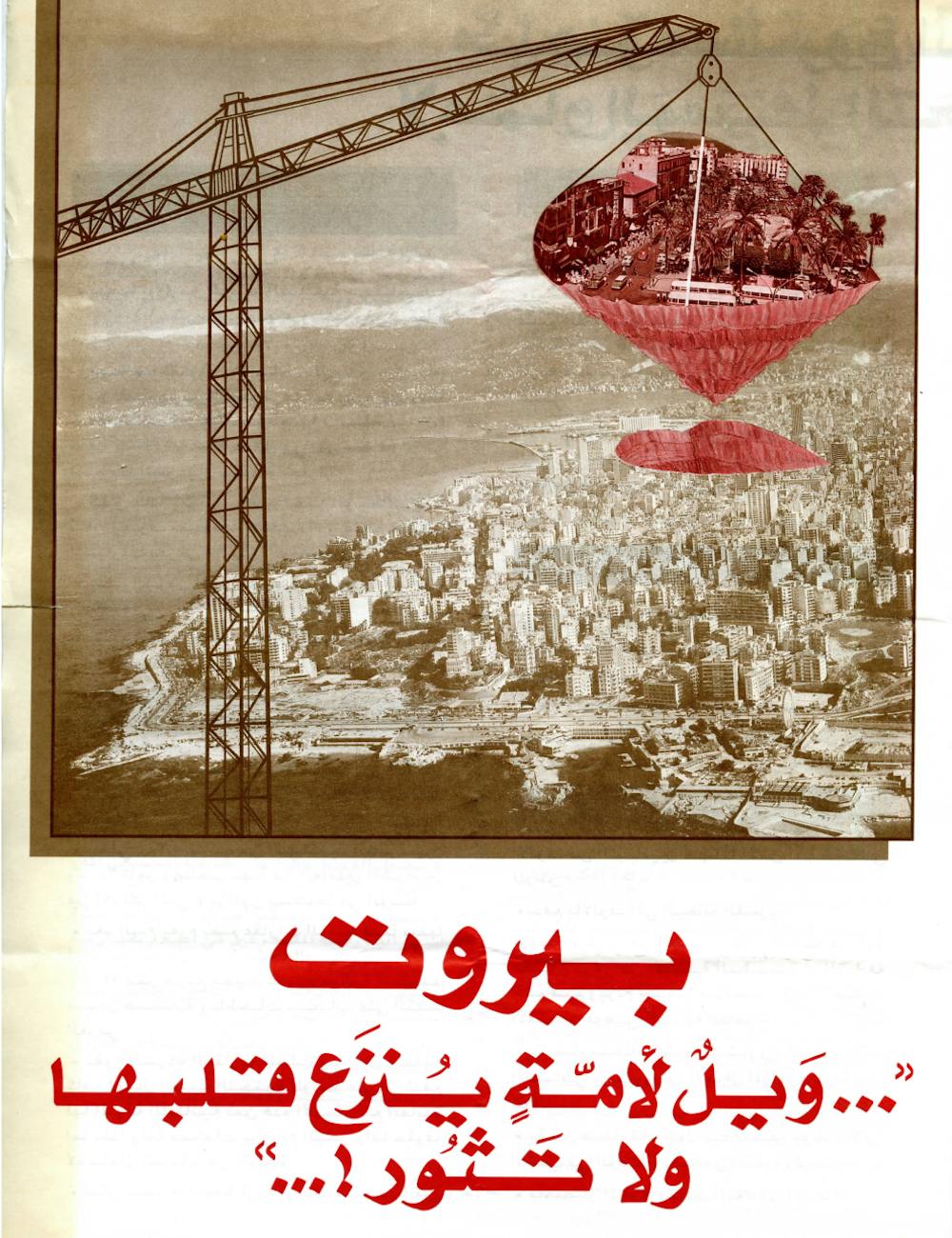

The front cover of a pamphlet published by the Association of Owners of Downtown Beirut. The caption reads: “Beirut… woe to the nation that removes its heart and does not revolt!”. Source: Arab Center for Architecture, Circa 1993. Rafik Hariri led the physical and economic reconstruction the country following the end of the Civil War. His transformation of downtown Beirut into a corporation and the reconstruction of this area into an elite enclave caused great consternation among the inhabitants of Lebanon. There were small mobilizations against the reconstruction that has remained a highly controversial development to this day.

Arsan, Andrew. “Intifadat Al-Istiqlal, or the Independence Uprising – The Moment That Passed [Chapter 1]. In Lebanon: A Country in Fragments by Andrew Arsan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, (2018).

Baumann, Hannes. Citizen Hariri: Lebanon’s Neo-Liberal Reconstruction. London: Hurst, (2017).

Baumann, Hannes. ‘Social Protest and the Political Economy of Sectarianism in Lebanon’. Global Discourse, 6 (2016), 634–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/23269995.2016.1253275.

Blanford, Nicholas. Killing Mr. Lebanon: The Assassination of Rafik Hariri and Its Impact on the Middle East. London: I.B. Tauris, (2016).

Chalcraft, John. “Islamism, revolution, uprisings, and liberalism, 1977-2011”. In Popular Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East, by John Chalcraft. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Ghandour, Marwan, and Mona Fawaz. ‘Spatial Erasure: Reconstruction Projects in Beirut’. ArtEast Quarterly Spring (2010).

Haugbolle, Sune. ‘Spatial Transformations in the Lebanese “Independence Intifada”’. The Arab Studies Journal, 14 (2006), 60–77.

Hourani, Najib. ‘From National Utopia to Elite Enclave: “Economic Realities” and Resistance in the Reconstruction of Beirut’. In City in the Twenty First Century: Global Downtowns, edited by Marina Peterson and Gary McDonogh, (2011).

Jaafar, Rudy, and Maria Stephan. ‘Lebanon’s Independence Intifada: How an Unarmed Insurrection Expelled Syrian Forces’. In Civilian Jihad: Nonviolent Struggle, Democratization and Governance in the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, (2000).

Khalaf, Samir. Heart of Beirut: Reclaiming the Bourj. London: Saqi, (2013).

Majed, Rima. ‘A View from the 1990s: Lebanon’s Street Politics in the First Decade After the Civil War (1989-2000)’. Centre for Lebanese Studies, (2020). https://lebanesestudies.com/a-view-from-the-1990s-lebanons-street-politics-in-the-first-decade-after-the-civil-war-1989-2000/.

Majed, Rima. ‘In Defense of Intra-Sectarian Divide: Street Mobilization, Coalition Formation, and Rapid Realignments of Sectarian Boundaries in Lebanon’. Social Forces, 99 (2021), 1772–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soaa076.

Makarem, Hadi. ‘Actually Existing Neoliberalism: The Reconstruction of Downtown Beirut in Post-Civil War Lebanon’. PhD Dissertation, London School of Economics, (2014).

Makarem, Hadi. 2015. ‘The Bottom-Up Mobilization of Lebanese Society Against Neoliberal Institutions: The Case of Opposition Against Solidere’s Reconstruction of Downtown Beirut’. In Contentious Politics in the Middle East, edited by Fawaz A. Gerges, (2015): 501–21.

Makdisi, Saree. ‘Laying Claim to Beirut: Urban Narrative and Spatial Identity in the Age of Solidere’. Critical Inquiry, no. 23 (1997).

Mango, Tamam. ‘Solidere : The Battle for Beirut’s Central District’. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2004. http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/30107.

Moumtaz, Nada. ‘Gucci and the Waqf: Inalienability in Beirut’s Postwar Reconstruction’. American Anthropologist, 125 (2023): 154–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13823.

Sawalha, Aseel. ‘The Reconstruction of Beirut: Local Responses to Globalization’. City & Society, 10 (1998): 133–47. https://doi.org/10.1525/city.1998.10.1.133.

Sharp, Deen. ‘Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon: Corporate Urbanization’. PhD Thesis, City University of New York, Graduate Centre, (2018).

Young, Michael. The Ghosts of Martyrs Square: An Eyewitness Account of Lebanon’s Life Struggle. Simon & Schuster, (2014).