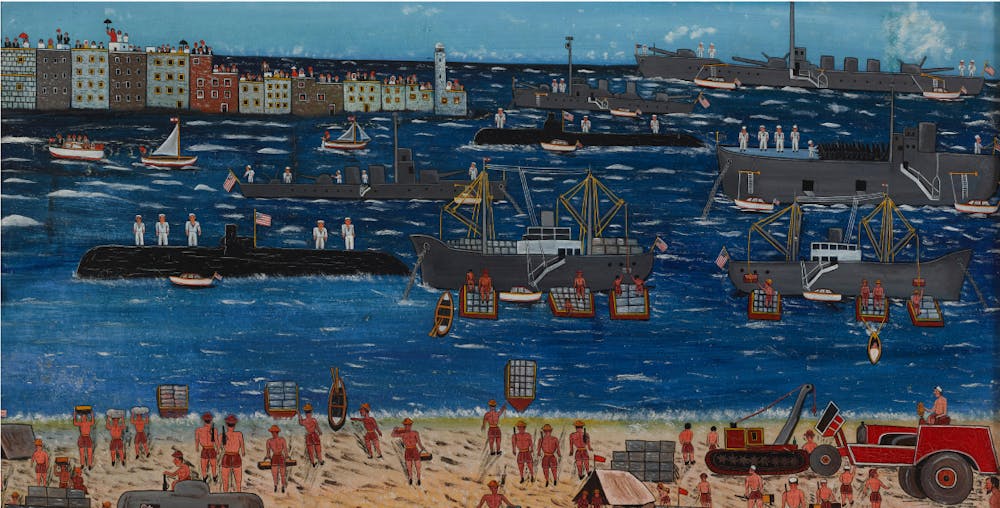

Marine Landing

1952-1958

The 1950s was a period of economic growth for Lebanon that furthered the role of Beirut as the financial and service center of the Middle East. Throughout the 1950s, popular mobilizations erupted. The mobilizations were led by labor unions, women’s groups and popular parties who actively exerted pressure on the state to improve their lot. Women’s strong participation in the Independence Crisis of 1943 propelled them forward in their struggle for equal political rights.

In 1952, shifting away from charity and education work, the Lebanese Council for Women spearheaded a well-organized campaign to lobby for full political rights, leading to the passing of a law on February 18, 1953, granting women the right to vote (Schubert 2020; Stephan 2010). At the American University of Beirut, students passionately supporting the new Arab nationalism, and organized a series of protests that culminated on March 27, 1954 in a major protest against the Baghdad Pact. The violent confrontation with the police, and numbers of casualties, prompted the administration to focus on restraining student mobilizations (Anderson 2001).

Politically, this period was dominated by Camille Chamoun (r. 1952-1958), a charismatic but highly polarizing president who held on to a pro-American foreign policy in the midst of rising Arab nationalism in the region. This policy alienated Lebanon’s Muslim political elites and divided the Christian ranks (Attié 2004; Karam 2021). Chamoun refused to cut diplomatic ties with Britain and France following the 1956 Suez crisis. Furthermore, Lebanon was the only Arab country to endorse the Eisenhower Doctrine (a Cold War presidential doctrine directed at containing Nasser and his allies).

In May 1958, Lebanon teetered on the brink of civil war. Camille Chamoun was determined to amend the Lebanese constitution in order to seek another term. The rigged parliamentary elections in 1957, covertly supported by the Americans, had ousted most of his opponents and insured a two-third majority in the parliament. His authoritarianism and pro-Western foreign policy alienated a significant cross-sectarian political faction opposed to his renewal, and who were intent on his removal. While in Iraq, the revolution that ended the rule of the pro-Western Hashemite royal family sent shock waves across the region. Following a frantic appeal by Chamoun, President Eisenhower ordered a military intervention in Lebanon in July 1958, the first of its kind in the region (Gendzier 1999).

Only recently have the popular mobilizations and their impact on state institutions in the 1950s attracted scholarly attention (Abu Rish 2014; Kardahji 2015; Tuffaro 2021). Were the 1958 events a revolution, an uprising, or a trial run for the civil war of 1975-1990? Experts agree that these events put the 1943 National Pact – the unwritten pact between Maronite and Sunni elites that ensured Lebanon’s independence from France – to the test. It revealed the structural weakness in the make-up of the Lebanese state, namely its political confessionalism. The politics of “no victor, no vanquished” invoked to ensure coexistence and national unity precluded critical reflection on the causes of civil strife. Accountability was waived to the side with a general amnesty declared in December 1958. Fouad Chehab, a consensus candidate supported by the Americans and British, embarked on strengthening the Lebanese state by championing state-led development with the belief that economic equity and social engineering may promote national cohesion.

In 1957, rigged parliamentary elections, covertly supported by the Americans, had ousted most of Camille Chamoun’s opponents and insured a two third majority in the parliament, allowing to seek the amendment of the constitution for a second term. His opponents, a significant cross-sectarian political faction, were opposed to his renewal, and were intent on his removal.

February 1958, the creation of the union between Egypt and Syrian (United Arab Republic, 1958-1961) sent tens of thousands of predominantly Muslim Lebanese across the border to welcome Gamal Abd al-Nasir which further polarized the situation in Lebanon. It heightened the fear among Lebanese Christians of possible interference from the United Arab Republic into Lebanon.

May 7, 1958, amidst mounting tension, insurrection broke out following the assassination of Maronite opposition journalist, Nasib al-Matni. Nationwide riots and demonstrations erupted in various parts of the country, demanding the resignation of Chamoun. Violent clashes and fierce fighting erupted in Tripoli, barricades appeared in the streets of Beirut, and Druze rebels in the Shouf area moved to attack the presidential palace in Beiteddine. The leaders of the insurrection included a large coalition of Sunni, Druze, Shi’i, and Christian leaders (zu’ama), who claimed that their rebellion was directed against the corruption and tyranny of Chamoun and his foreign policy, which went counter to Arab nationalism. Nonetheless, civil strife turned into sectarian violence. Fighting continued over two months between the opposition’s rebels and Chamoun’s partisans supported by the police. The Lebanese army stood on the side, following the order of Army Commander Fouad Chehab who refused to engage the army.

Students rioting outside Beirut's American University, and military and police were on the other side of the gates trying to hold rioters back. Beirut Students Riots (1954) - YouTube, British Pathé.

O'Halloran, Thomas J, photographer. American soldier in a tank, Beirut, Lebanon / TOH. Beirut Lebanon, 1958. [7/0/58] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2023630524/

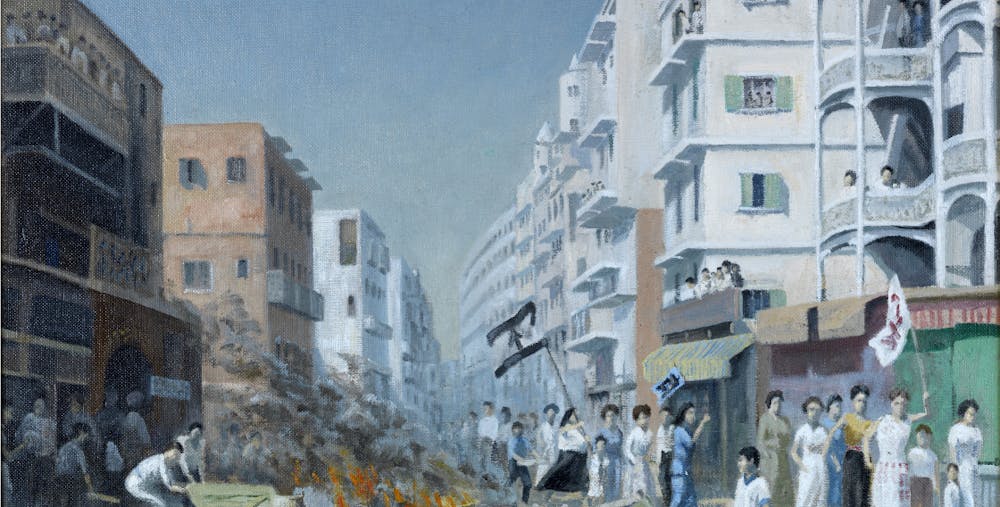

Khalil Zgheib, Untitled. 1958. Samir Moubarak Collection, Lebanon

E. Harrison, Women Protest in Furn el-Chebbak, 10 July 1958. Collection Philippe Jabre, Lebanon

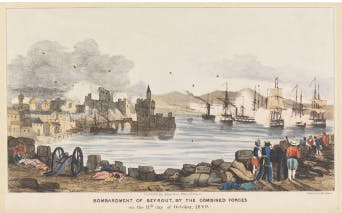

Khalil Zgheib, Marine Landing. 1958. Saleh Barakat Collection, Lebanon

Abu-Rish, Ziad Munif. “Conflict and Institution Building in Lebanon, 1946–1955.” Ph.D. diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2014, 58–109.

Abu-Rish, Ziad. “On Power Cuts, Protests, and Institutions: A Brief History of Electricity in Beirut.” Jadaliyya, April 22, 2014. www.jadaliyya.com/Details/30564/On-Power-Cuts, -Protests,-and-Institutions-A-Brief-History-of-Electricity-in-Beirut-Part-One.

Anderson, Betty S. The American University of Beirut. Arab Nationalism and Liberal Education. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001.

Attié, Caroline. Struggle in the Levant. Lebanon in the 1950s. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2004.

Barakat, Halim Isber. Lebanon in Strife: Student Preludes to the Civil War. University of Texas Press, 1977.

Ilyas al-Bawari, Tarikh al-haraka al-‘ummaliyya wa’l-niqabiyya fi lubnan: 1947–1970. Beirut: Dar al Farabi, 1980.

Gendzier, Irene. Notes From the Minefield. Columbia University Press, 1997.

Karam, Jeffrey G. The Middle East in 1958. Reimagining a Revolutionary Year. London: I.B. Tauris, 2021.

Kassir, Samir. Beirut. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

Khuri, Fuad I. From Village to Suburb: Order and Change in Greater Beirut. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975.

Owen, Roger and Roger Louis. A Revolutionary Year: The Middle East in 1958. IB Tauris, 2002.

Riedel, Bruce. Beirut 1958. How America’s War in the Middle East Began. Washington: The Brookings Institute, 2020.

Traboulsi, Fawwaz. A History of Modern Lebanon. London: Pluto Press, 2007.

Tufaro, Rossana. “Labor and Conflict in Pre-War Lebanon (1970–1975): A Retrieval of the Political Experience of Factory Committees in the Industrial District of Beirut.” Ph.D. diss., Universita Ca’Forscari Venezia, 2018.