Ghandour Factory

1967-1975

The years leading to the Civil War (1975-1990) in Lebanon were rife with social unrest, cultural ferment, and political radicalization. The Chehab era had failed to deliver on its promise of social reform, and significant disparities still existed between Beirut and Lebanon’s southern and northern regions. Mass rural migrations to the city and rapid urbanization resulted in Beirut’s "poverty belt", dense suburban neighborhoods that lacked sanitary infrastructure and basic amenities.

Lebanon, in the 1960s and 1970s experienced the widest and most longstanding wave of social conflict in its post-colonial history (Tufaro 2020). There was a remarkable development in urban labor mobilizations and the student movement between 1968-1975. By the 1970s, and in the face of severe police repression, strikes and protests gathering thousands of participants became commonplace.

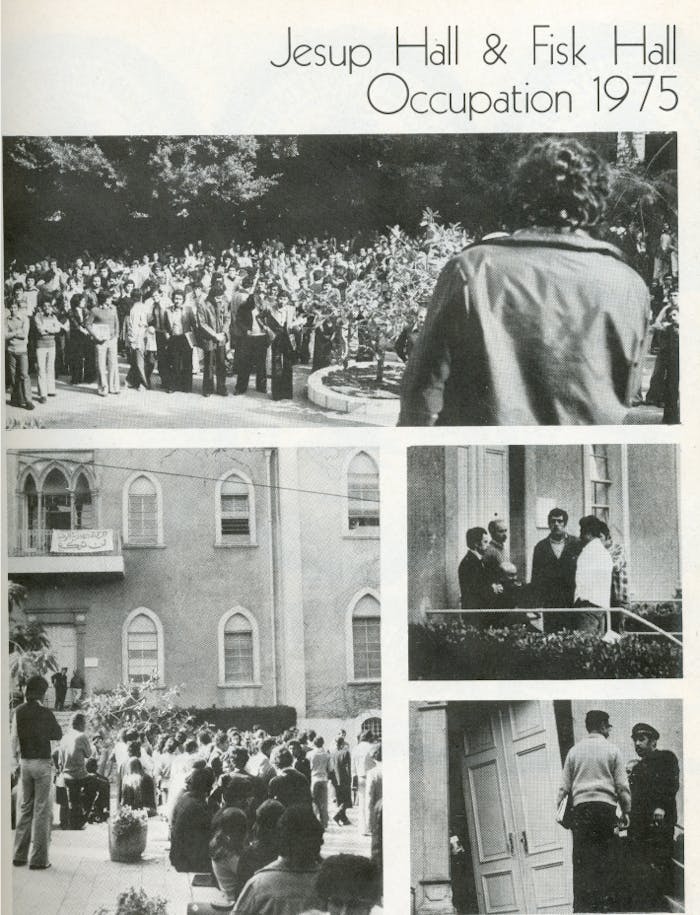

The wave of contestation among students engaged all universities, notably the Lebanese University (in 1971 and 1972) and the American University of Beirut (in 1971, 1972, and 1974). Protests also extended to high school students from public and private schools (Barakat 1977; Farsoun 1973; Rabah 2009).

Massive workers’ strikes took place in the years leading up to the Civil War, the most important being the Ghandour Factory Strike (1972), the Tobacco Farmers’ Strike (1973), and Saida’s Fishermen’s Strike (1975) (al-Buwari 1987). However, these protests did not lead to national unity. As Samir Kassir put it, Lebanon was bedevilled by many cleavages on the eve of the Civil War.

The 1967 Arab defeat against Israel and the 1971 suppression of Palestinian resistance in Jordan transferred the weight of the Palestinian resistance to Lebanon, where it found widespread popular support. Lebanon became the base for the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), turning Lebanon’s southern border with Israel into a battlefield. Around the Palestinian resistance coalesced different progressive and nationalist parties, which by 1975 had enhanced their implantation among workers, peasants, and university students.

Another mobilization movement was spearheaded by Imam Musa al-Sadr (1928-78), a Shi’i cleric who rallied Lebanon’s Shi’a communities around the Movement of the Deprived, asking for greater participation in Lebanon’s economy, culture, and political life (Chalcraft 2016). In turn, the presence of the PLO in Lebanon led to the active militarization of popular militia linked to the Christian parties.

Ghandour Factory is a family-run manufacturer specializing in food processing, biscuits, and sweets. The two plants in Chiyah and Choueifat recruited many young and unemployed rural migrants.

November 3, 1500 working men and women held a strike and demanded that: “No worker should be dismissed after the end of the strike; the payment of an increase in the cost of living and a periodic increase; allowing workers to join the Confectionery Workers Union; preventing the qualitative deduction from the wages for overtime hours, which is an hour and a half; making the annual leave 17 days; paying wages for days of work-related emergencies; giving Choueifat workers transportation wages and abolishing methods of coercion to work that violate the provisions of the Lebanese Labor Law” (Boutros 2015; Tufaro 2020).

The management refused to respond to the workers’ demands.

November 11, the workers assembled before the Chiyah plant to convince their co-workers to join the strike. The security forces violently intervened to disperse the workers, resulting in two deaths (Youssef al-Attar and Fatema Khaweja) and many wounded among workers and security forces (Jirmanus 2017).

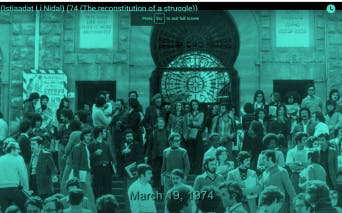

Image still for the film “74: The Reconstitution of a Struggle (Istiaadat li nidal)” by Raed and Rania Rafei

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UODKmF6q7MM

Students in 1974 demonstrated against a tuition increase at the American University of Beirut. For 37 days, they occupy university offices. With the Lebanese student revolt of 1974 as their starting point, filmmakers Rania and Raed Rafei direct an absorbing documentary on the core issues of revolution and democracy. In addition to a meticulous re-enactment, they include theatrical improvisations in which today's activists give their interpretations of the student leaders' actions in 1974.

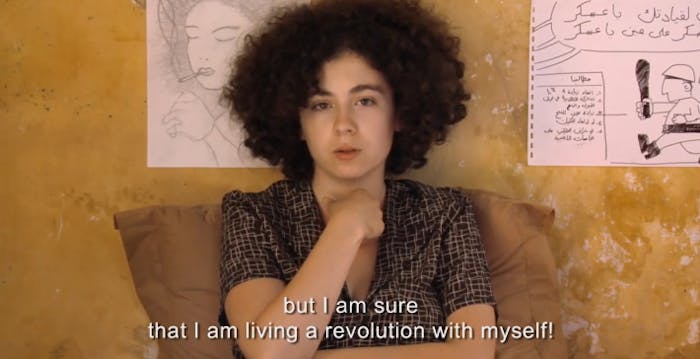

https://afeelinggreaterthanlove.com/

In her directorial debut, Mary Jirmanus Saba deals with a forgotten revolution, saving bloodily suppressed strikes at Lebanese tobacco and chocolate factories from oblivion. These events from the 1970s, which held the promise of a popular revolution and women’s emancipation, were erased from collective memory by the country’s civil wars. Rich in archival footage from Lebanon’s militant cinema tradition, the film reconstructs the spirit of that revolt, asking of the past how we might transform the present.

Still: Student Demonstration against Police Brutality: 22 April 1972 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gIWKhOmegBA

Aref al-Rayess, Yawm al-Jami’ah al-lubnaniya, 1968 Collection Saradar, Beirut Lebanon http://www.saradarcollection.com

In the aftermath of the June War of 1967 and the Israeli attack on Beirut’s International Airport (December 18, 1968), university students, especially at the Lebanese University, demonstrated massively and were brutally repressed. This painting shows a policeman beating a student whose head is floating against a red background.

Rayess said about this painting: “I painted this over one night. I intentionally did not want it to be a work of art. As long as the human being and human thought are not valued in this country where its students are attacked, we will no longer make art.”

Student protest was a major feature of this period. AUB Archive Collection

Barakat, Halim I. Lebanon in Strife: Student Preludes to the Civil War. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1977.

Bardawil, Fadi. Theorizing Revolution, Apprehending Civil War. Leftist Political Practice and Analysis in Lebanon (1969-79). London: LSE Middle East Center series, 2016.

Boutros, Joelle. “Azmat Ma‘āmil Ghandūr: ‘Indamā kāna al-Qānūn Yahmī al-Tard al-Ta‘asufī,” al-Mufakkirat al- Qānūnīyyah, last Modified August 21, 2015, http://www.legal-agenda.com/article.php?id=1219

al-Buwari, Elias. Tarikh al-ḥaraka al-‘ummaliyya wa-l-niqabiyya fī lubnan 1971-1980 [History of the Worker and Syndicate Movement in Lebanon 1971-1980]. Beirut: Dār al-Farābī, 1987.

Farsoun, Samih. “Student Protests and the Coming Crisis in Lebanon.” MERIP Reports, no. 19 (August 1973): 3-14.

Hudson, Michael. The Precarious Republic. Modernization in Lebanon. Boulder and London: Westview Press, 1985.

Jirmanus Saba, Mary. “What the Use of a Strike Archive. On Image Archives, Surplus, and Solidarity,” Critical Time 5,3 (December 2022): 663-687. DOI 10.1215/26410478-10030274

Kassir, Samir. La guerre du Liban. De la dissension nationale au conflict regional. Paris, Beirut: Karthala, 1994.

Keppen, Thomas Davis. “The Tobacco Farmers Uprising in the Press.” M.A. thesis, American University of Beirut, 2021.

El-Khazen, Farid. The Breakdown of the State in Lebanon, 1967-1976. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Owen, Roger, ed. Essays on the Lebanon Crisis. London: Ithaca, 1976.

Rabah, Makram. A Campus at War. Student Politics at the American University of Beirut 1967-1974. Beirut: Dar Nelson, 2009.

Traboulsi, Fawwaz. A History of Modern Lebanon. London: Pluto Press, 2007.

Salibi, Kamal. Lebanon 1958-1976. Crossroads to a Civil War. London: Ithaca Press, 1976.

Salibi, Kamal. A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. London: I.B. Tauris, 1988.

Tufaro, Rossana. “Also, a Class (Hi)story: working-Class Struggles and Political Socialization on the Eve of Lebanese Civil War, Confluences Méditerranée, no. 1(2020/1): 21-35.