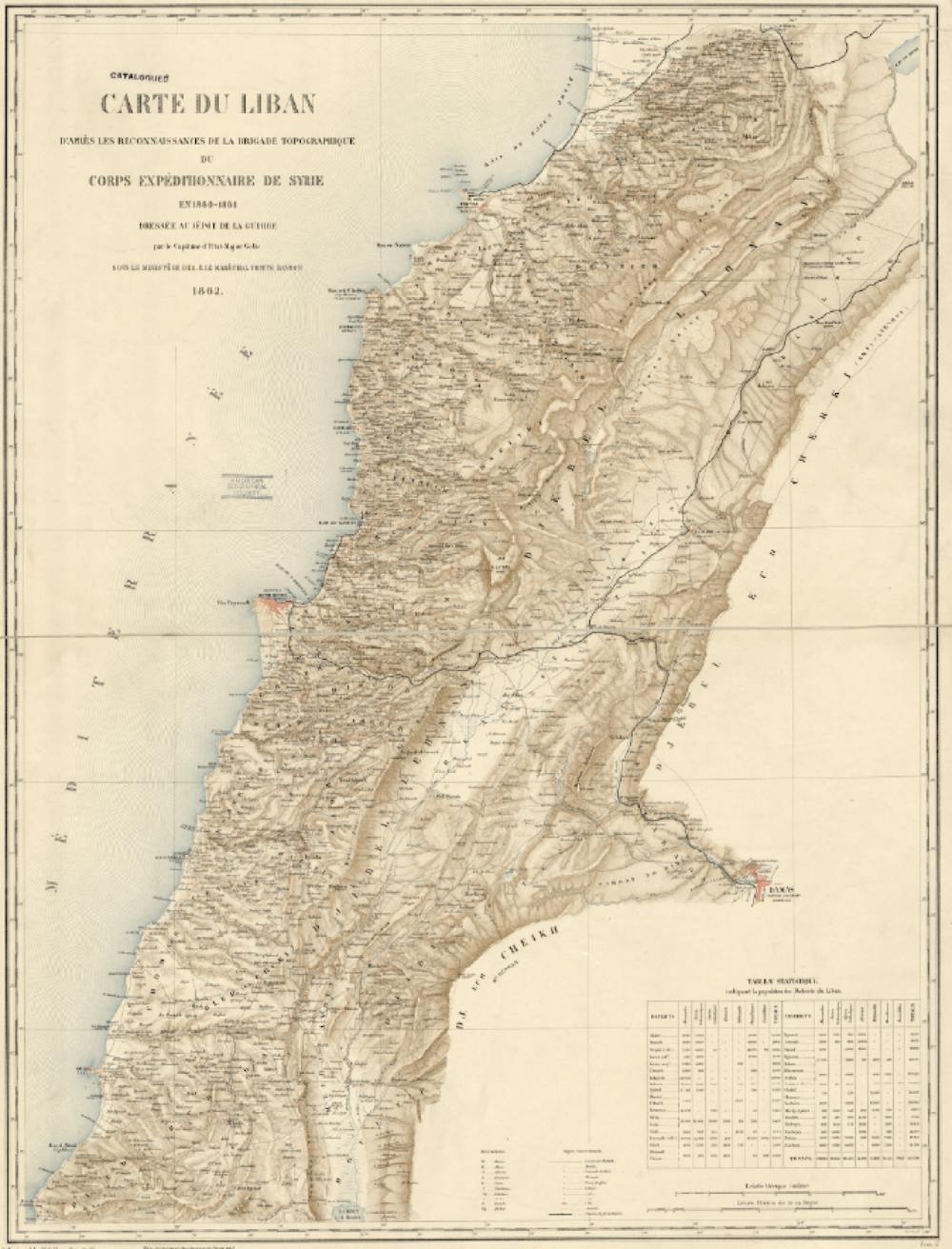

In January 1821, Abdallah Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Saida, asked for an advance payment of the annual tax from Emir Bashir. Unable to fulfill this obligation, Emir Bashir passed on the extra tax burden to the Christian peasants of Mount Lebanon’s northern districts (Metn, Kisrawan, Batrun, and Jbayl). He spared the Druze-dominated southern districts of Mount Lebanon (Shuf, and the four regions (iqlim) of Jezzin, Tufah, Kharrub and Jabl al-Rihan), for fear of alienating the Druze lords.

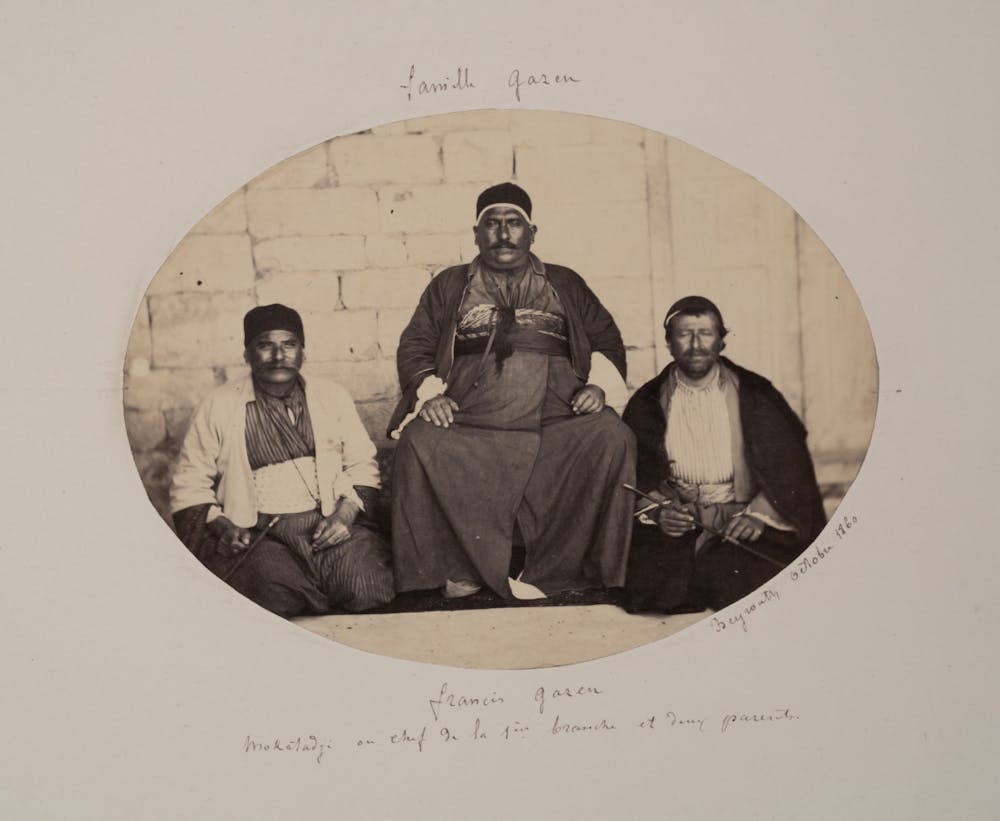

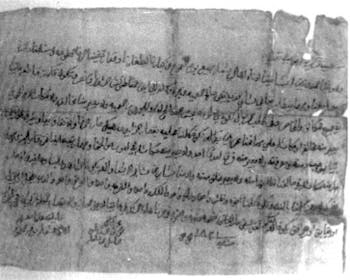

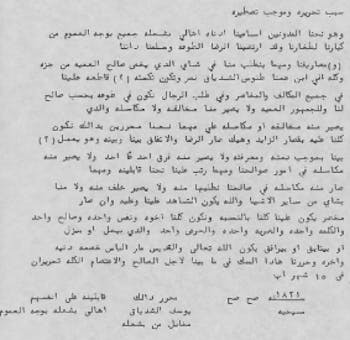

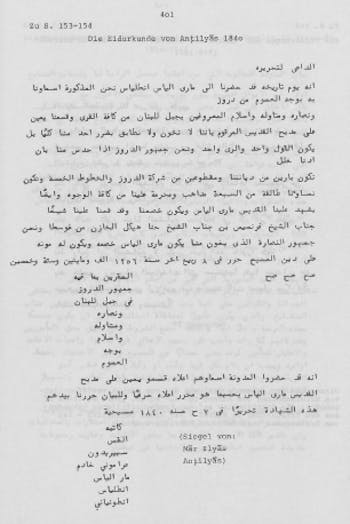

The peasant resistance to Emir Bashir’s exorbitant tax demands consisted of two movements: the Ammiyya of Antilyas (winter-spring 1821) and the Ammiyya of Lihfid (summer 1821). The Maronite archbishop, Yusuf Istifan (1759-1823), led a group of Maronite commoners, with some Druze and Shiites, and gathered at the Church in Antilyas (Havemann 1983). They swore to resist the payment of taxes and demanded that the land and poll taxes be levied once a year. Historians estimate that more than 6,000 rebels were present at this meeting (Havemann 1983). They vowed not to betray one another and to struggle together for the common good. They produced a convenant between them. In the covenant, the insurgents emphasized that they were acting for the sake of the general interest and public welfare (al-salih al-ummumi) (Havemann, 1983). Villages that were taking part in the movement elected deputies (wukala) from the ranks of the commoners, who negotiated for them.

Faced with the commoners’ resistance, Emir Bashir went into exile to Hawran with his retinue, at which point he renegotiated his return with the Ottoman governor and enlisted the support of the Druze and Maronite notables. He rejected all the commoners’ demands and reimposed his tax policy on Mount Lebanon’s northern districts. The commoners in Jubayl, Batrun, and Akkar rose again and gathered in Lihfid, a village in the district of Batrun. They demanded to be treated on equal terms with the Druze concerning taxation and other matters. They also called for the tax collectors assigned by the ruling Emir to be from the same respective region. With the support of the muqata’jis, Emir Bashir brutally crushed the resistance in a battle near Lihfid, putting an end to the insurgency. One leader of the movement, Antonious Abu Khattar al-Ayturini, a notable historian of Mount Lebanon, was caught and tortured. He died soon after. Maronite Archbishop Istfan died of poisoning in 1823. While the 1821 ‘Ammiya failed to change the conditions of Mount Lebanon’s peasants, it was the first articulation of a majority community that undermined the traditional ties of kinship and loyalty between the commoners and their feudal lords.